51: The Latest News on the Oldest Life

A quick plug before starting the show: we now have a Patreon website where you can give monthly donations for bonus perks, such as a new monthly show called Hometown Geology. Paid members can listen to the show, vote on topics and even suggest topics. That website is patreon.com/bedrockpodcast Now back to the show.

Last episode, we explored a claim for the oldest fossil on Earth. We’ve seen many similar claims since Season 1: diamonds from Australia, iron from Canada, and phosphorus from Arctic islands. All these older claims are heavily debated or completely disproven. All until last episode. Let’s recap: what is this special rock? Why might it hold fossils inside?

On the Greenland tundra, in a cold stretch of rocky hills near the Arctic Circle, there sits a boulder the size of a small couch. The boulder is very old, 3.7 billion years old, March 11 on the Earth Calendar. This old rock has a beautiful striped pattern: pale gray shifting to black, like an ombre pattern on a blanket or skirt. Pale gray to dark black, pale gray to dark black. This pattern is not only beautiful, but it tells a story of a lost world. The gray and black layers formed at the bottom of an ancient sea. The black layers were once dark mud, like the bottom of the modern ocean. Once in a while, a storm shook things up, bringing in pale sand from shallower waters. If you repeat this process over and over, you’ll make a pattern of pale and dark layers, just like our special Greenland boulder. You’re looking at a slice of ancient seafloor.

That’s great, Dylan, but what’s so special about old sea mud? If you’re looking for fossils, old sea mud is the perfect place to look. Have you ever picked up a handful of dark mud from a lakebed or beach? If so, you’ve likely gotten a whiff of life and death: a pungent, rotting smell that slaps your face. The color and smell of that mud comes from millions of tiny dead bodies: an organic sludge. If you bury that sea mud and squeeze it into a stone on the Greenland tundra, the dark sludge will transform into dark minerals of graphite, an old mineral friend of the show. That’s right: the graphite inside your pencil and in this ancient boulder, might have come from old dead bacteria, the primordial ooze. It’s not as visually appealing as a skeleton or a footprint, but give it a break: it’s the oldest fossil!

Or is it? Every other fossil candidate we’ve seen has been picked apart by science, a string of question marks or duds. But ever since our special Greenland boulder was discovered in 1999, no serious challenger has arisen. No one has come forward and said: here’s why this stupid boulder ISN’T Earth’s oldest fossil. In fact, very recent evidence seems to support the fossil idea. Today, we focus on the last 10 years of research on this special Greenland boulder, the strongest evidence yet for life on Early Earth, including papers written just a few months ago.

Part 1: A Closer Look

Let’s return to our special striped boulder, the rock that just might have Earth’s oldest fossils. This boulder was described in 1999 by Minik Rosing, a geologist born and raised in Greenland. We described Minik and his discovery last episode, so what’s the story as we head into the 2000s? At first, not much. You might expect a dogpile of other researchers tearing him apart, but not really. Even the most skeptical researchers would say that Minik’s 1999 fossil spot was still OK, was still a viable fossil. In my mind, I imagine several geology professors mud-wrestling at a conference, kicking and tearing at each other’s hair. As Minik walks by, the fighters would stop, give him a grinning thumbs-up, then continue to beat the snot out of each other.

And yet, for a long time, no one returned to Minik’s fossil boulder. This lack of attention was a double-edge sword. Sure, no one was disproving the fossil idea, but without a closer look, there would always be an asterisk, a qualifier. This boulder probably has Earth’s oldest life, it could be a contender. This hedging continued for years until 2014, over a decade after Minik’s discovery.

This team was from Tohoku University in Japan, led by Yoko Ohtomo. Our old friend Minik was also on the team, providing boulder samples and giving the research his blessing. So what did Yoko and her team find in 2014? What evidence could strengthen the fossil argument?

Yoko Ohtomo, a graphite guru

Yoko’s team focused on the graphite crystals inside the boulder. As a reminder, let’s recap what we learned about graphite last episode. Graphite is made of pure carbon. If you squeeze a carbon-rich bacteria hard enough, it will turn into carbon-rich graphite. The problem is, there are alternate graphite recipes that don’t need life. You can squeeze any carbon-rich item into graphite if you try hard enough. The point is: graphite alone is not enough to say life was here- you need more proof.

Here's where Yoko’s team come in. They looked at the microscopic shapes of the graphite crystals. Perhaps there would be a difference between graphite from fossil life, and graphite made in other ways. Yoko’s team had brand-new toys to play with: Transmission Electron Microscopes or TEM. Don’t worry, that name won’t be on the test. Here’s what you need to know. A normal microscope uses visible light to see crystals. A TEM microscope uses tiny electrons instead. This means that you can see much smaller features in much greater detail, stuff you can’t see with light alone.

For example, in 1999 Minik looked at his old Greenland graphite under a regular microscope. He could see the dark crystals were about 5 microns long, the size of a bacteria. That’s it. In 2014, Yoko’s team could zoom in 1000 times smaller, to 5 nanometers. To wrap your head around that idea, imagine this. You’re looking up at an airplane, very high in the sky, just a speck. You can tell that it’s plane shaped, but that’s it. Now imagine you have a pair of very good binoculars. If you look at the plane now, you can see more details like the logos, the wing shape, etc. You can figure out how and where that plane was made.

On a microscopic scale, that’s what Yoko and her team were doing with the Greenland graphite. If they could see the microscopic crystal structure, they could tell if it had been squeezed from bacteria, or something that wasn’t alive. What did they find?

Zooming into the crystals, Yoko found strange patterns: tubes and polygons, irregular shapes. These were not tiny fossils themselves, but were strong evidence that the graphite had come from life. Here’s how. In its purest form, graphite forms regular sheets of organized carbon, squeezed into a proper order. However, life is not orderly. We have lumps and bumps, spiral DNA and squishy cells. Even if you squeeze life’s beautiful chaos into graphite crystals, some of those irregularities will remain behind on a nano-meter scale. If you’re having a rough day, remember this: the world can crush and change life as hard as it wants, but it’s hard to completely erase it.

Graphite from different locations in Greenland. Left is “messy” irregular graphite from seafloors, possibly from fossils. Right: “ordered” vein graphite. From Ohtomo et al., 2014, Nature Geoscience.

Just to make sure, Yoko checked out graphite in other Greenland rocks, ones that were way too hot to have fossils inside. Just as she expected, these non-fossil graphites had neat, orderly layers of carbon, too neat and tidy to be made from life. These prim and proper graphites were very different from the messy, chaotic graphites inside our special boulder. Finally, folks had figured out a way to visually compare fossils from fakes at a microscopic level. The 2014 paper was a huge win for Minik Rosing, Yuko Ohtomo, and their team. But the good news was just beginning.

Part 2: The Crystal Time Capsule

We’ve been sticking our noses in the nano-meter world of graphite crystals, smaller than a single bacteria. Let’s zoom back out and review what we’ve learned.

We’re looking at a large striped boulder sitting on the Greenland tundra. The stripes were once layers of mud at the bottom of an ancient sea. The mud has been squeezed into mudstone. The carbon-rich bacteria inside have been squeezed into carbon-rich graphite crystals, the oldest fossils on Earth.

That’s a lot of squeezing, a lot of change that’s happened to this poor rock over billions of years. Wouldn’t it be nice if just a small pocket had escaped all that squeezing? Imagine a time capsule discovered inside a ruined building. The building has been leveled, nearly destroyed, but the time capsule would preserve fragile, delicate pieces of a world long gone. Perhaps the same thing can happen inside ancient rocks.

In 2017, a team from Copenhagen, Denmark, described tiny time capsules inside our special Greenland boulder. These capsules weren’t made by bacteria, they didn’t have tiny dates stamped on them, saying: Please open me in 3.7 billion years. But these time capsules did preserve tiny, delicate features unseen in any of our previous fossil candidates.

The 2017 paper was published in the journal Nature, the highest place a geologist can go. The Copenhagen team was led by Tue Hassenkam and included our friend Minik Rosing, who first described the special fossil-rich boulder in 1999. So what did they find?

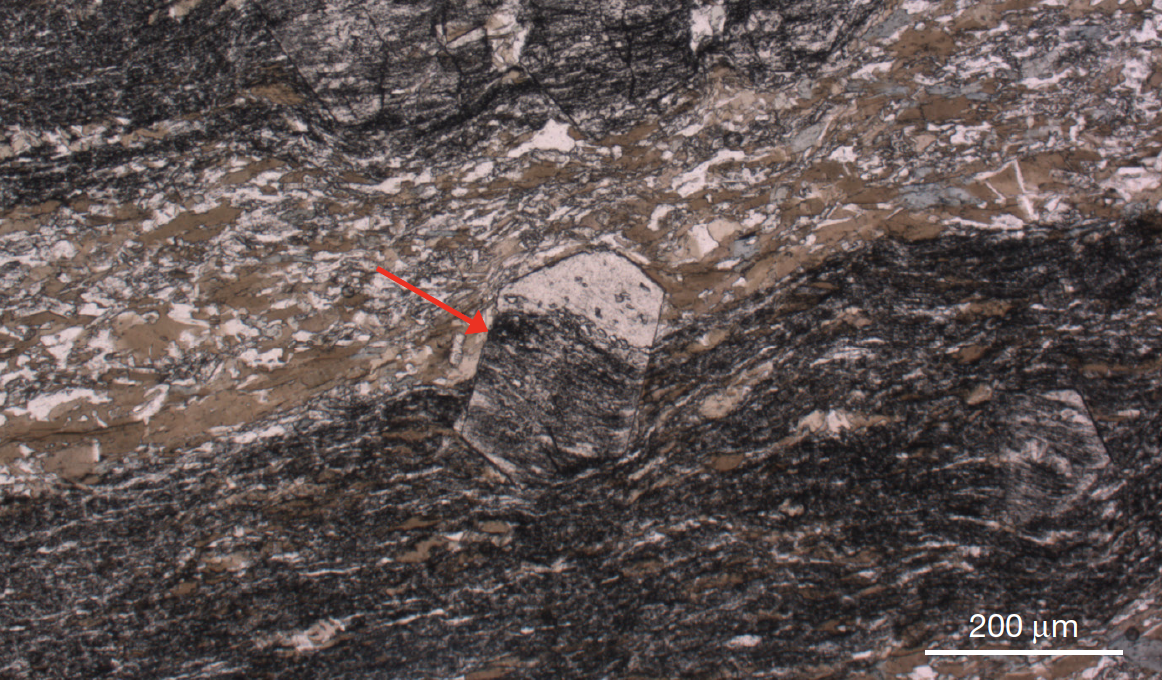

Hassenkam looked closely at the layers inside the boulder: black and gray, black and gray. Every now and then, something different would show up: large red crystals with geometric shapes like hexagons or octagons. The crystals were literally giant stop signs saying: “hey, check me out!” These red crystals are an old friend of the show since Season 1, character actors who pop up every few episodes. We learned all about them in Episodes 38 and 39. Folks, let’s welcome garnet back on the show.

Garnet is a famous gemstone- hard, round and usually red, though it can come in nearly any color. On a personal note, garnet is my birthstone, and one of my favorite minerals: tough, strong, and reliable. Beautiful, but not as flashy as a diamond. In geology, garnet forms deep underground, under intense heat and pressure. Every time we’ve seen a garnet on this show, it tells us that the rock has been metamorphosed, pressure-cooked.

You might be scratching your heads. Dylan, we’re looking for time capsules, pockets of ancient rock that have escaped metamorphism. A pressure-cooked rock doesn’t sound like a great place to look. That’s a fair point, but consider this. In Season 2, all the rocks we have are pressure-cooked, baked hundreds of degrees and squeezed nearly to oblivion. We don’t have much of a choice here. In such tortured rocks, the best time capsules are crystals that are tough, strong, and reliable. Crystals that can survive the heat and pressure. Crystals like garnet.

If you’re still confused, let’s rewind the clock back 3.7 billion years ago, back to our ancient mucky seafloor. As the mud is buried, it crystallizes into stone. In most places, this transformation occurs normally: dark sea mud turns into dark mudstone. However, in a few corners, there’s a little extra squeezing, a little extra heat. This pressure-cooking recipe is just right to make a garnet crystal, a speck of red in layers of dark mudstone. The red garnet grows very slowly. As it grows, it gobbles up little flecks of mud and dead bacteria around it. These dark flecks and specks are now trapped inside the red garnet like flies in amber, or like papers in a time capsule.

A garnet that has “swallowed up” surrounding mud and dark graphite as it grew. From Hassenkam et al., 2017, Nature.

Here’s the important part. As the rock is squeezed further, all the fossils outside the garnet time capsule are squeezed into graphite crystals, pure carbon. All the fossils inside the garnet are safe and sound. Since 2017, the Copenhagen team have been cracking open these time capsules, 3.7 billion years old. What treasures did they find?

Part 3: The Record Player

Let’s start with what they didn’t find. The Copenhagen team didn’t find bacterial cells, either living or dead. No critters came wriggling out of the rocks like a sci-fi monster trapped in ice. Garnet is a good time capsule, but it’s not that good.

Instead, we’re still looking at the ground-up remains of dead critters, organic mush. Not as exciting as a skeleton or even a tiny bacterial body, but there are still some secrets to find. For the past two episodes, we’ve been talking about graphite, graphite, graphite. Pure carbon. But as important as carbon is to life on Earth, it’s not the only ingredient in your body. Think about the iron in your blood, the calcium in your bones, etc. You are a walking periodic table, and so is every other creature, including bacteria.

So when I tell you that the Copenhagen team found carbon attached to other elements inside our tiny time capsules, you should get excited. It’s not a fossilized body, but it’s more complex than anything we’ve seen yet. It’s another clue that life was here.

Let’s start with how the team made this discovery, because it’s really cool.

In Part 1, we talked about light microscopes vs electron microscopes. Light microscopes shoot light at a sample. Electron microscopes shoot electrons at a sample.

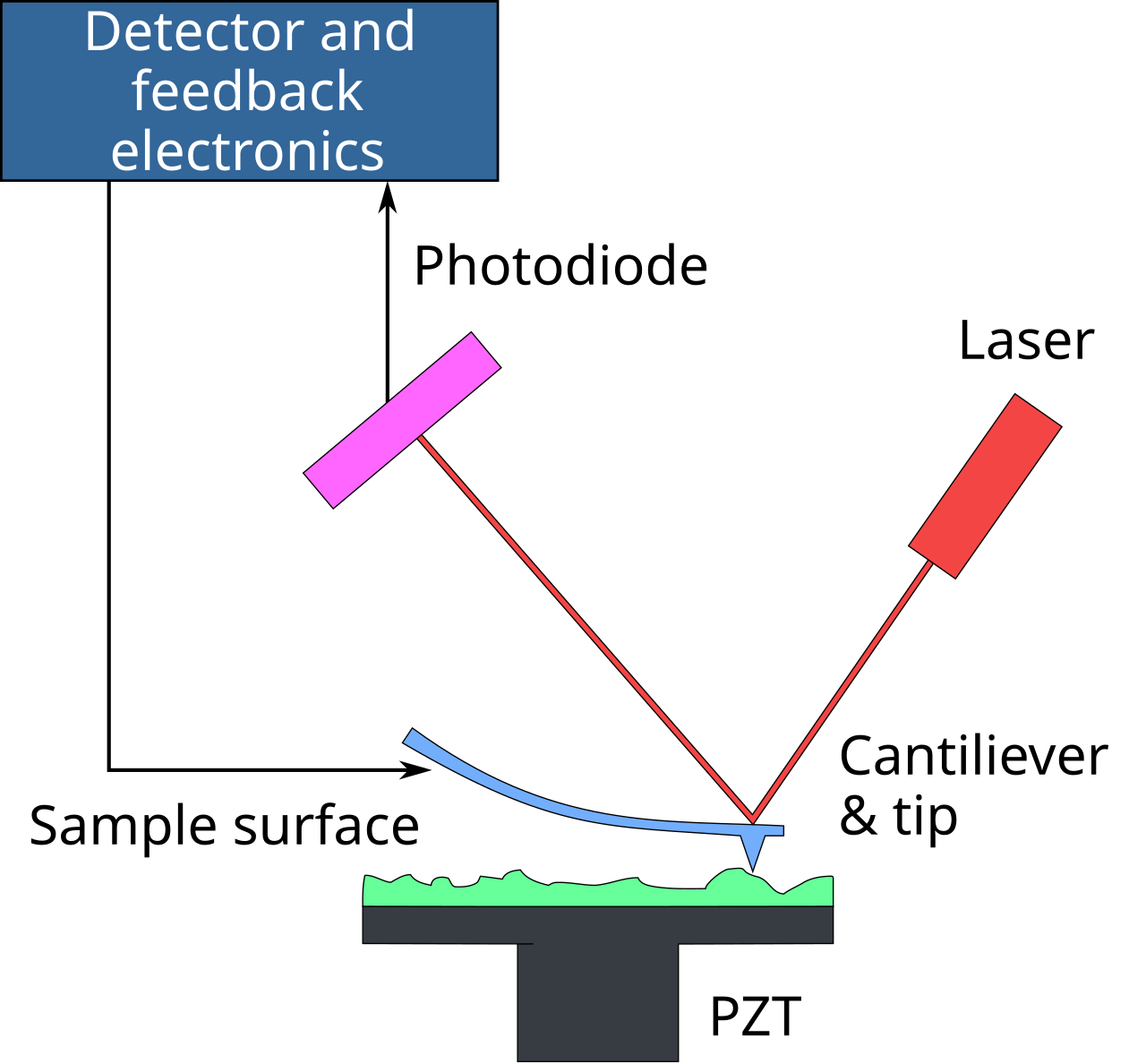

The Copenhagen team used a force microscope, which sadly does not shoot the Force at a sample. Sorry to you Star Wars fans out there. Instead, a force microscope is more like another product of the 1970s and 1980s: a record player. If you have a record player, dust it off and check it out for this next section. If you don’t have one, check one out online or ask your parents. Most record players have a long skinny arm tipped with a long skinny needle. You would gently place the needle on the record, which would turn a physical surface into an audio signal.

A force microscope does something similar. Like a record player, there’s a long arm with a long needle which passes over a surface. As the arm sweeps over the sample, it records high and low areas, slowly making a map on the nanometer scale. If you attach other instruments on this arm, you can learn even more about your sample, like what atoms are present and how they’re connected. Which brings us back to our fossil quest.

OK, here’s where we’re at in the story. The Copenhagen team is looking at a carbon-rich rock, likely the oldest fossils on Earth. They’ve found tiny crystal time capsules inside the rock that might have even more evidence for early life. After playing these time capsules like microscopic records, what did they find?

A heat map of carbon-nitrogen bonds trapped inside a garnet “time capsule”, 3.7 billion years old. Hassenkam et al., 2017, Nature.

They found carbon atoms attached to nitrogen atoms. Ok, cool, but what does that tell us? Nitrogen is a very important ingredient in life, though it often gets overshadowed by its’ big brother carbon. Every single critter on Earth has a decent amount of nitrogen inside. For example, nitrogen is the 4th most common atom in your body: from your DNA to your muscles to your urine. Nitrogen will appear many times in the series. For today, just consider it an accessory to carbon.

Finding carbon by itself can be a fossil clue, but it can also be a red herring. We’ve seen such red herrings time and again in this series: crystals of diamonds and limestone that have nothing to do with life. That’s why the nitrogen is so important. Finding a lot of carbon and a lot of nitrogen connected together- that’s a stronger sign of life. However, it’s not fool-proof by itself. There are still other recipes to shove carbon and nitrogen together.

Layers of graphite in the garnet crystal “time capsule” (grt) match the mud layers outside the garnet. Harding et al., 2025, Nat. Comms. Earth & Environ.

Fortunately, the Copenhagen team have some supporting evidence. Fortunately, both are fairly easy to explain visually- we don’t have to do too much more chemistry.

Let’s zoom back out to our big Greenland boulder. As I’ve mentioned a few times, this boulder has well-defined stripes, black and gray. These stripes were once layers of mud on an ancient seafloor. If our ancient Greenland carbon came from dead critters on the seafloor, you would expect the carbon to follow the same striped patterns. In short, where you find layers of mud, you should also see layers of carbon. And that’s exactly what the Copenhagen team found: an ancient parfait of mud and crushed corpses.

Finally, in March 2025, just a few months ago, the Copenhagen team published a new paper revisiting carbon isotopes. I’m not going to review the ins and outs of isotopes again, check out last episode for more on that. But here’s what they found: carbon inside the tiny crystal time capsules had a stronger signature for life than outside the time capsules. Just as you would expect. Who knows what else we’ll find inside these garnet time capsules with even fancier tools.

So after all that, have we found Earth’s oldest fossils? So far, no paper has challenged the Copenhagen team, but this is still cutting-edge research. Their last paper was published in March 2025, so the jury is still deliberating. Here’s my personal take. When I started researching this Greenland location, I was fully expecting it to be just like the rest: promising at first, but ultimately a dud or a mystery. However, I haven’t seen a valid rebuttal since this rock was first described in 1999. That’s a much better track record than any fossil candidate we’ve seen. What’s more, the latest evidence using the latest techniques appears to support the idea of fossils, not deny them.

I’m writing and releasing this in December 2025. Who knows how well this will age in a few years? Maybe someone will find a new flaw in our special Greenland boulder and it’s back to the drawing board. So be it. Maybe even more fossil evidence will come, even stronger clues for life. Even better. I’m done hedging and hemming around. For now, the Bedrock podcast will consider 3.7 billion graphite crystals from the Greenland tundra Earth’s oldest evidence for life. Break out the champagne, it’s time to celebrate a hard-earned victory.

Summary

3.7 billion years ago, bacteria lived and died at the bottom of the sea. Dead bacteria were entombed in mud and buried deeper into the Earth. The cells and DNA were eventually squeezed into an organic sludge. As the mud crystallized into stone, most of this sludge was pressure-cooked into pure carbon. But in a few special pockets, this sludge was protected by time capsules: tiny red crystals of garnet. These capsules don’t preserve any bodies or DNA, but they do preserve a hint of former life: carbon and nitrogen hand-in-hand. It’s not much, but this faint chemical signature in an old striped boulder is our best candidate for Earth’s oldest fossil. Next episode, we approach the end of our Greenland quest, with one final fossil fable. You might ask: what could possibly be next? We’ve found Earth’s oldest fossils.

Thank you for listening to Bedrock. If you like what you’ve heard today, you can donate on our Patreon or our website- you’ll find links in the description. Special thanks to Shout-Out Patrons like Simone Templar and Arturo Dent for supporting the show. If you can’t donate, just tell a friend, rate the show, or leave a comment. It always makes my day, and that one person could be you. You can drop me a line at bedrock.mailbox@gmail.com. See you next time, and rock on!