52: The Thing in the Ice

The date is September 2016. The place: the University of Southern California, in sunny Los Angeles. It’s the first week of school, and everything is a bustling chaos. The boulevard is packed with students scurrying beneath huge oak trees and red brick buildings. If you look up at one of these buildings, you might just spot a grad student looking back at you. He has a swoop of sandy hair, a patchy ginger beard, and a pair of thick red glasses.

This student was me, your host Dylan Wilmeth, 10 years ago.

To finish this story, let’s switch to my perspective. I’m sitting at my laptop in my office. An email pings into my inbox. It’s a group email, sent to a dozen researchers around the world. The recipients, including myself, all study fossil pond scum: bacterial colonies that include some of Earth’s oldest fossils.

The email has only one word. That word was Hmmm, an “h” followed by a few “m”s, a sound of ponderous thought. There was also a document attached: a PDF of a brand-new research article in the journal Nature, the highest place a geologist can write. The authors claimed to find Earth’s oldest visible fossil in Greenland: ancient pond scum you can hold in your hand and see with your eyes. If they’re right, these fossils would be hundreds of millions of years older than the next contender. Big news if true. But was it true?

As I read the article, replies start to ping in the group email, each just one word: “Hmmm”, over and over. After reading the article, I lean back and say “Hmmm” as well. It’s not a “Woohoo!” of support, it’s not a “Boo” of dissent. Just a thoughtful “Hmmm.”

After 10 years, these perplexing Greenland rocks are still hotly debated. Are they Earth’s oldest visible fossils, the first traces of life that don’t need a microscope to see?

Or are they just funny-looking rocks? Today, we listen to both sides of this debate.

Episode 52: The Thing in the Ice

Happy New Year! I hope your holidays were safe and warm and pleasant. If not, you can always find such a space here. Some housekeeping before we start.

After holiday break, the show should be back on a biweekly schedule. That might change as the semester ends, because once again, I’m on the job hunt. My university graciously gave me a one-year extension as a visiting professor, but that one year will end in April. I’m still looking for professor jobs, but I’m also considering a completely new career in science communication. Basically, taking what I do here at Bedrock and doing it professionally. That job could be a science writer or editor. That job could be for a university, a publication, a company, or a government program. If you know somebody who needs a voice for science, please consider me interested.

On a similar note, I finally started a Patreon last month. For $2 a month, you can hear bonus episodes of a new series: Hometown Geology, where I focus on rocks of certain cities and landmarks around the world. If you want a free taste, check out last episode on Grand Rapids, MI: my current hometown. For a few dollars more, you can vote on future episodes, or suggest topics yourself! Voters just decided on Asuncion, Paraguay’s capital as the next topic, and are currently leaning towards Mt. Katahdin in Maine after that. If you want to hear more, just search for Bedrock Patreon online.

OK, stepping off my soapbox, let’s return to the show.

Since Episode 36, we’ve been exploring the oldest rocks in Greenland. That’s 16 episodes, far more than any previous location. I understand if you’re getting antsy, but there’s good news. This is our penultimate episode on Greenland- there’s only one more to go. Then, we’re off to brave new lands and brave new times.

This episode is one I’ve been anticipating for years. In Episode 1, I introduced myself as a researcher of fossil pond scum. And now, 50 episodes later, I finally get to talk about fossil pond scum, my actual job: let's go!

But before I get ahead of myself, let’s step back and review where we are in time, and what we've learned about ancient life and ancient Greenland.

In time, we’re sitting 3.7 billion years ago, March 11 on the imaginary Earth Calendar, the end of Season 2. In Season 1, Earth started off as a ball of molten rock, pelted with asteroids. By Season 2, Earth has cooled down and is mostly covered with oceans. There’s lots of water, lots of carbon, and the temperature is just right. By 3.7 billion years ago, most scientists are sure that life is around. But proving it is another matter.

Most rocks from this ancient time have been eroded or melted away. The few rocks that remain are either too warped to preserve fossils, or never had fossils to begin with. The faint glimpses we’ve seen are highly debated: carbon in Australia, iron in Canada, phosphorus on Arctic islands. They might be traces of life, but as long as there are alternate recipes, there’s always going to be question marks at best.

Which brings us to SW Greenland. These rocks are the most extensive we’ve yet seen: the area of Rhode Island or Luxembourg. They’re also the most well-preserved we’ve yet seen, though they’re still pretty messed up, baked to at least 500 C or 900 F. They also preserve the right environments: seafloors rich in water and carbon, the building blocks of life.

There’s a reason we spent so much time here: it’s an oasis of rocks and data and maybe life.

In the last two episodes, we discussed our best fossil candidates yet, 3.7 billion years old from SW Greenland. Even I was surprised- I was expecting other researchers to pick these little guys apart, but as of 2025, the latest evidence seems to support the presence of life. And yet, despite the strength of these fossils, they’re not much to look at. No bones, no teeth, no footprints. Not even the tiny bodies of bacteria. Instead, all that remains are microscopic shavings of graphite crystals, the same material in your pencil tip. If you want to visualize last episode’s fossils, just crush your pencil into a piece of paper and make some black specks. Now imagine those specks are 5 microns long, invisible to the naked eye. These black specks might be the oldest fossils, but they’ve been through the ringer.

Now that we’ve finally found fossils, our new quest is to find even cooler ones: bigger, more well-preserved, something that looks like life. Which brings us to today’s episode.

10 years ago, a group of scientists showed the world a lumpy rock from Greenland and claimed it was a fossil. Not some microscopic pencil shavings, not invisible carbon chemistry, but a fossil you can see and hold in your hand. The type of fossil that I study every day. Or are they fossils at all, are they just another dud? That’s today’s debate.

As you can imagine, I have some personal stakes in this debate. I haven’t studied these Greenland rocks, but I know researchers on both sides, colleagues with passionate opinions. I have my own opinions, but like previous episodes, I’ll keep a neutral voice until the end. I’ve been waiting for this episode for years, let’s finally dive in.

Part 1: From Scum to Stone

Before we start the Greenland debate, before I even describe the rocks themselves, I need to set up some background. If these old lumpy rocks are fossils, they’re unlike any fossils we’ve seen on the show, and they deserve some introduction.

In Episode 49, I laid out four types of fossils we’ll see on this show, in order of excitement. Let’s compare what we’ve seen in previous episodes to what we’re going to see today. If you’re on a binge and just heard Episode 49, feel free to skip to 17:18, but I’d recommend this for a refresher.

At the bottom of the totem pole are indirect traces: rocks that were left behind by life, but don’t hold any bodies. These include rocks like Banded Iron Formation with beautiful rusty tiger stripes. They’re beautiful, and possibly indicate life, but they don’t always preserve life itself. Think of these rocks as life’s leftovers. Check out Episodes 32 and 48 for more info.

Next up is organic carbon: the pulverized remains of dead bodies. Imagine taking leaf litter on the forest floor, squeezing it into a black sludge, then squeezing it even further into black coal, then even further into black graphite crystals of pure carbon. Yes, this was once a living thing, but there’s no trace of the fun stuff left. Such graphite crystals are the oldest accepted fossils we met last episode. As I said: cool stuff, incredibly important, but not a lot to look at.

Next up are microfossils: the tiny bodies of bacteria. Finally, something that looks like a living thing! Bacteria come in many shapes and sizes, from spheres to threads to sausages. It’s easy for life to make these simple shapes, but it’s also easy for them to form chemically without life. So far, we haven’t seen a definitive microfossil on the show, but in Episode 33 we met some rusty, straw-shaped objects in northern Canada, which are still debated. We won’t see microfossils today, but keep your eyes peeled in future seasons.

Which finally brings to the last and most exciting candidate: big fossils, ones you can see with the naked eye. You’re probably imagining dinosaur skeletons, human footprints, or seashells on the beach. Sadly, none of these will appear on this show, maybe some shells in the last season. No, the only life present 3.7 billion years ago were bacteria and their cousins.

But wait, Dylan, you might say: bacteria are microscopic. How can we make a big, visible fossil out of a microscopic critter? The answer is teamwork. One bacteria makes a microfossil, but when you gather trillions of bacteria together, they form very visible features, things you’ve undoubtedly seen at least once in your life. I’m talking about microbial colonies of pond scum.

Pond scum might seem mundane, even gross. But for me, a patch of pond scum is like a miniature rainforest or coral reef: trillions of individuals and thousands of species making something much larger. From small things, big things grow.

That’s the end of the recap from Episode 49. Let’s head into new material.

OK, you might say: I can see how lots of bacteria can make carpets of pond scum, but how does that pond scum get fossilized? I thought soft, squishy stuff doesn’t usually survive. You’re right- this is why we don’t usually see fossil skin or organs or feathers unless you’re very, very lucky. However, there is a simple recipe for fossilizing bacteria, one that’s probably happening in your home right now. I have two words for you: hard water.

If you’re a homeowner or a plumber, you might be groaning or nodding along. If you don’t know, what is hard water? Why do we care and how does it fossilize bacteria?

Hard water isn’t actually hard or solid like ice. Instead, this water has lots of dissolved crystals and minerals inside. When hard water evaporates, these crystals are left behind, forming thin pale crusts of limestone on your faucets, bathtubs, tea kettles and boilers. It’s a nuisance that must constantly be kept in check. If you’re not sure if your place has hard water, just add some soap! If you have hard water, very few bubbles will form and your water will turn cloudy. If you have soft water with few minerals inside, you will make a thick, rich bubble foam, and the water will remain clear.

Let’s take this idea of “hard water” and return back to geology. Just like your household appliances, hard water will also crystallize tiny bacteria over time. For another visualization, imagine making rock candy. All you have to do is put a stick in sugar water, and crystals will soon cover it. The longer you wait, the more crystals grow. The same thing happens to pond scum in hard water. Over time, the floppy pond scum crystallizes into a solid stone, something you can shatter with a hammer. In other words: a fossil.

There are variations on this recipe, but that’s the basic theme: hard water can turn soft pond scum into a hard fossil, usually in limestone. These fossils have a special name. I briefly mentioned this name in Episode 49, but it will be the keyword of this episode and a constant earworm until the end of the show. Fossil pond scum is called a stromatolite. One more time: stromatolite. That’s a mouthful, so geologists usually shorten that name to “strom.”

Now that we have a name for fossil pond scum, what the heck does it look like? If you want to hunt for stromatolites, what should you look for?

Part 2: A Field Guide to Stromatolites

The classic image of a stromatolite is a small dome rising from the seafloor, resembling an anthill or a giant gumdrop covered in slimy pond scum. If you slice through this dome, you’ll see many thin layers like tree rings: the fossilized remains of older pond scum colonies. I’ve put a few pictures on our website: bedrockpodcast.com. But how can we tell a real stromatolite fossil like this from potential imposters?

Let’s start by picking apart the word “stromatolite”. In ancient Greek, “stromato-” means layered, and “lite” means rock. So this fancy Greek word just means “layered rock”.

At first, the definition of “layered rock” doesn’t sound very helpful. Many rocks have layers, and they have nothing to do with life! Dumping sand and mud on the seafloor will make layers, lava flows will pile into layers, and even squeezing rocks deep underground will create zebra stripes.

So what makes the layers in a stromatolite special? How do we know life made them?

First, the type of rock is important. As I mentioned last section, stroms usually form in hard water. The hard water in your home usually forms limestone if you let it build high enough. The same is true of strom fossils: the vast majority are made from limestone or its’ bratty sister dolomite, which we met in Episode XX. We will meet some oddballs in later seasons, but for now, the limestone family is enough to remember.

Second, the shape of the layers. Layers in many rocks are crisp and straight. If you keep pouring sand or mud into a cup, gravity will pull them into flat, horizontal stripes. Sometimes wind or waves will push sediment into angles, but even these are sharp or mildly curved. But layers inside stromatolites are often wrinkled, crinkled, and uneven.

They rise up into domes, cones, and columns, defying the boring flatness of sand or mud. Some stromatolites are less dramatic, but upon a closer look, even these flatter forms are gently wrinkled like water-soaked paper.

But even if you find a rock with weird, wavy layers, we must still be cautious. There are other ways to form a layered dome that don’t need life. Many lifeless recipes involve metamorphism, squeezing and contorting rocks deep below Earth’s surface. Sometimes, you can twist a formerly flat rock into domes, cones, and columns that are eerily similar to microbial fossils. Don’t forget this idea, it will be important later in the episode.

I could list a dozen ways to tell a real fossil stromatolite from an imposter, but it will be more fun to learn on a case-by-case basis. Before heading into our first strom debate today, a few final notes. Stromatolites and lookalikes will be a permanent part of the show until our final season: they are literally Earth’s most abundant fossils for 90% of its’ history. I’ve given a basic definition of a layered microbial dome, but they come in many shapes and sizes, from tiny branching bushes smaller than a fingernail, to titanic columns wider than a car and taller than a human. If you give bacteria enough time, they can create incredible structures. I’ve said it once, and I’ll say it again: from small things, big things grow.

That being said, most stromatolites are the size of your hand, and form simple, sensible domes. With that in mind, let’s finally meet our first strom candidates of the show. Are they fossils, or something else?

Interlude: Time on the Tundra

Imagine yourself on the Greenland tundra: lots of rocks, very little vegetation. We’re sitting on a wide patch of snow on a hillside. We’ll be sitting here a while, so let’s imagine a comfy chair so our butts don’t get wet. In front of us, about half a mile, is a steep drop off down, the precarious edge of a large cliff. Beyond the cliff is a wide panorama: a huge, cracked ice sheet spilling down into pale blue lakes surrounded by boulder-strewn hills. It’s a beautiful sight. But we’re here for the rocks next to us, not way off in the distance

We see a few geologists hike around our snowpatch, collecting rocks, writing in notebooks, enjoying lunch and the sights of nature. Who they are isn’t important, so we’ll let them pass. The scientists walk away into the distance, leaving us all alone once again. Let’s press fast-forward. The sun rises and sets faster and faster, low on the Arctic horizon. Winter blizzards pass in flashes of white, quickly followed by brown and gray summers. Occasionally, we’ll see more geologists skitter by our snowpatch, like ants hopped up on sugar. But most of the days we’re alone. How many years have passed? 5, 10, 20? It’s hard to tell out on the tundra, with no cities, no roads, no internet to guide us. It’s calming and unnerving at the same time.

But as the years move on, we do see changes. The glaciers begin to recede back, uncovering more hills and lakes. It’s not a lot yet, just the edges of the mighty ice sheet, but it’s noticeable. Larger snowpatches like ours begin to shrink smaller and smaller.

The old snowpatch site, now melted to show two potential fossil sites (A and B). From Nutman et al., 2016, Nature.

Eventually, all of our snow has melted away, and we’re left sitting on naked rock. Let’s press stop. It’s 2015 or 2016, around 50 years have passed in our time skip.

A new crew of geologists is approaching our hill, armed with smartphones and GPS units.

As they approach, we see a familiar face lead the way: a man with dark hair, a salt-and-pepper beard, and black, bushy eyebrows. This is Dr. Allen Nutman, from the University of Wollongong in Australia. Nutman was a constant companion from Episodes 40 to 48. He has probably written more papers on ancient Greenland than any living geologist, at least 100, though don’t quote me on that. Beside him are two constant companions: Drs. Clark Friend and Vickie Bennett, also from previous episodes. One can imagine mixed emotions on their faces: the loss of snow is a worrying sign of a warming climate, but it has exposed a rare opportunity to find new, er, ancient rocks.

And the rocks they find are certainly interesting, but the question remains: are they fossils? Are they stromatolites? Let’s start by describing these funky rocks.

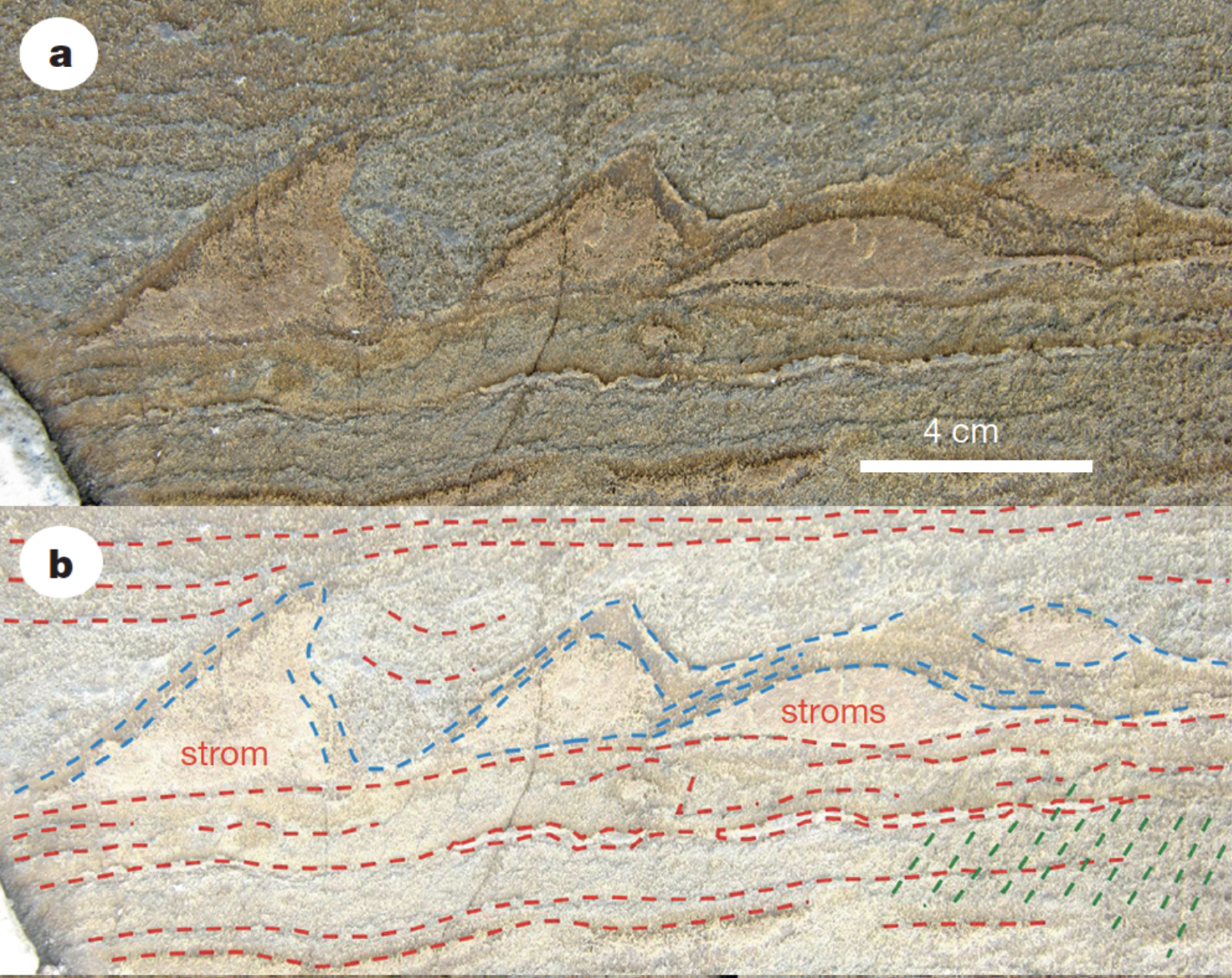

Boulder “A” from the image above, as seen on foot. Note the downward-pointing triangles in the middle gray layer. These are the possible stromatolites in question. If so, the rock has been flipped “upside-down”. The white cobble is roughly hand-sized. From van Kranendonk et al., 2025, Earth-Science Reviews.

As the snowpatch melted away on the Greenland hillside, fossil candidates showed up in two locations. Two couch-sized boulders, around 50 paces apart. You could walk from one to the other in under a minute.

The first thing you’d notice about these boulders is layering. Each rock is covered in thin horizontal stripes of tan and gray. Most stripes are the width of your finger, some are the width of your hand. There’s no precise pattern to the stripes: you’ll see many thin layers, then one thick band, then thin thin thick, etc. Think of a supermarket barcode, just tan and gray instead of black and white.

There’s one other difference between our striped boulders and a barcode. In a barcode, the layers are straight as an arrow, flat and boring. From a distance, the boulder stripes also appear flat and boring, but come closer. You begin to see imperfections in these layers, thin wrinkles and contortions like pages of an old, waterlogged book.

And then you see something very different. A few layers are not flat at all. They form distinct triangles pointing downward, like cartoon fangs or shark teeth or ice cream cones. These triangles aren’t that big, just a couple of inches or centimeters, but they are distinctive. Once you spot one downward triangle, you soon find others crowded on the same layer.

If you’re having trouble visualizing this, please check out our website: bedrockpodcast.com, we’ve got lots of pictures. To summarize: imagine a barcode from the supermarket, with thick and thin horizonal lines. Now make those lines slightly wrinkly. Finally, give a few of those lines little vampire fangs pointing down. These weird triangles are the fossil candidates, the subject of a decade of debate.

The picture that started the whole debate. This image is from the right side of Boulder A from the figure above, rotated 180 degrees. Nutman et al., 2016.

First things first, what type of rock is this? Is it sandstone or mudstone, or something else? I’ve described it, but let’s give it a name.

This rock is dolomite, a new friend of the show we met in Episodes 47 and 48. If you’re new, here’s the 30-second lowdown. Dolomite is in the limestone family, usually forming on warm seafloors. It’s very common in ancient rocks, but very rare today. In either case, it usually crystallizes on surfaces like rock candy, or pesky crusts left behind by hard water. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? It should. Since dolomite is a sister of limestone, it’s a good candidate for turning pond scum into stromatolites. We will see many dolomite fossils in future seasons.

OK, so our boulder is made of dolomite. This means we’re looking at a slice of ancient seafloor. Good place to find fossils! This dolomite also forms weird, lumpy layers. The question now is: what were those lumps?

That’s the question of the day, and there are two schools of thought, two sides of this great debate. Let’s meet our contenders.

Part 3: The Two Teams

Now before I introduce these teams, I want to lay some ground rules. We’ve tackled many debates on this show, and we strike a balance between entertaining and respectful. Old debates from the 1800s are easy to poke fun of, since everyone’s dead. But this Greenland debate is only a decade old. Careers and reputations are on the line, and you can feel the passion and sometimes anger when reading these arguments. Emotions are still high.

Furthermore, this is an area inside my wheelhouse. It’s easy for me to gloss over volcano debates or Moon debates, but I literally study fossil pond scum for a living. I want to get this right. I personally know people on both sides of this debate- they’ve helped my career, and you’ll meet them in a few minutes. I respect these people professionally, even if I disagree on some points, but I want to keep those relationships alive. On that note, let’s meet our two teams. I’ll briefly introduce three new researchers here. There’s a method to the madness: Two folks will be big players in Season 3, and two folks have played important roles in my life. Still, I understand that’s a lot of info in an already long episode. If you want to skip right to the debate, head over to XX:XX. Otherwise, let’s get to know some folks.

Our first team is Team Nutman, AKA Team Fossil. They think the weird dolomite lumps were once bacterial colonies, stromatolites, fossil pond scum. He is the first author on most of these papers, but I have to briefly introduce another important teammate: Dr. Martin van Kranendonk.

Martin is a professor at Curtin University in Perth, Australia. Martin has been researching ancient rocks since the 1980s, especially in the vast Outback of Western Australia. These are rocks we’ll see soon in Season 3, so I’ll wait until then for a full biography. Here’s the important point: Martin is an expert on stromatolites, on fossil pond scum. If there’s a stromatolite somewhere in Australia, he’s probably seen it, and probably published on it. My personal connection to Martin was on a multi-week field trip through the Outback: the Astrobiology Grand Tour. Under his guidance, we saw more strom fossils than most folks see in a lifetime, and also managed to escape horizon-spanning bush fires. For more stories from that trip, check out my interviews from Season 1. Everyone I’ve interviewed was on that same trip, and we have Martin to thank for a great adventure.

In 2016, when Team Nutman found weird lumpy rocks in Greenland, they came to Martin van Kranendonk for assistance. It was a meeting of minds: Greenland experts meeting a stromatolite expert. Together, they published a paper in Nature, claiming to find Earth’s oldest stroms. This is the paper from the cold open, the paper I read as a young grad student. The paper that kicked this whole debate off, that made everyone go “Hmmm.”

Speaking of which, let’s meet Team Opposition. These folks are not fans of the fossil idea. They think there are other recipes to make these weird, lumpy rocks. There are many people on this team, but two major players. The first is Dr. Abigail Allwood, who works at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Like Martin, Abigail is a stromatolite expert, especially in Season 3 rocks from Australia. Like Martin, I’ll save her biography for next season, but I’ll give one teaser. Abigail is a lead scientist on the Mars 2020 Rover mission, looking for life on other worlds. That might sound strange, but if you think about it, looking for alien life is like looking for ancient life: you need to be damn sure you’re not looking at a false image. Which brings us back to Team Opposition.

Abigail wrote the first critique of the Greenland fossil idea, the first skeptical paper. But the mantle has transitioned to another researcher. I know there’s been a lot of names already, but this is the last one, and he is an important player. Meet Dr. Mike Zawaski. Unlike Martin or Abigail, Mike won’t appear in Season 3, so I will cover more of his background.

All of Mike’s degrees have been from Colorado institutions: a Bachelor’s from Western Colorado in 1994, a Master’s from Northern Colorado in 2007, and recently, a Ph.D. from UC Boulder in 2021. He is currently a visiting professor at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado. He has an interesting spread of projects, including Martian sediments and Incan ruins in Peru. But his most cited work is a 2020 paper arguing against fossils in Greenland. Definitely Team Opposition.

I’ve only met Mike once, but it was a very memorable meeting. We were at a conference in Honolulu, Hawaii, both speaking in a stromatolite session. Scientists get very hungry at these events, forming gangs roaming the streets for a quick lunch break. Mike and I merged into the same foraging party and quickly hit it off. At the time, I had just been awarded my first professor job, the job I currently have in Michigan. I was ecstatic to get the gig, but also terrified: I had never taught a real lecture before, talking to a class for an hour or more. I was asking everyone I met for advice. Mike Zawaski, who I had just met, gave me some of the best. I still use his tips and tricks today, three years later, from small discussion groups to personal answer cards. If you’re one of my students listening to this show, you have Mike to thank for our classes. He made me a better teacher before I even started. I know Mike listens to the show because he’s commented on our website. If you’re listening- thank you, and we should do an interview sometime.

That’s a lot of names to dump, but here’s the broad picture. I’m going to focus more on Teams than individuals as we wrap up.

There are two teams fighting over our lumpy Greenland rocks. Team Fossil has Allen Nutman, an old friend in Season 2, and Martin van Kranendonk, who will star in Season 3. Team Opposition has Abigail Allwood, another future star of Season 3, and Mike Zawaski, who has recently made his name in Greenland.

Again, I had hoped to make this all one episode, but it’s been 40 minutes and we haven’t even gotten to the debate yet. I guess I just got excited now that we’re actually in my home turf. I’d rather give this the time it deserves than rush. So next time, we’ll immediately start the debate fresh, instead of 40 minutes into an already long episode. With that in mind, let’s wrap things up.

Summary

Stromatolites are the most common fossil for 90% Earth’s history, the best records of microbial life. We have only begun to scratch the surface of these guys, there will be plenty more to come. Trust me, this is my favorite corner of geology- it’s literally my job. This episode introduced what might be the oldest stroms on Earth, 3.7 billion years old in Greenland. They might not look like much, hand-sized triangles on a few lonely boulders, but if they’re fossils, these are the first structures we can see with the naked eye. The first visible signs of life on Earth. But that’s a big claim, and there are many folks willing to dispute it. Next time, we’ll see Team Fossil and Team Opposition duke it out, and learn how to tell a fossil from a dud in one of the biggest debates of our age. Until then, rock on.